The origins of one particular genre of Hip Hop

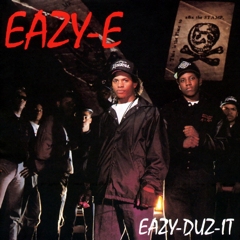

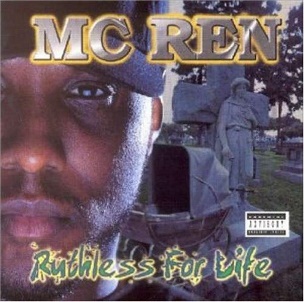

I have personally created a decent amount of music in my life. Many of my most important influences were involved with Ruthless Records and started with N.W.A. Ruthless records was comprised of Black and Brown artists from Los Angeles, California. The Ruthless Records heyday was from around 1988 to 1998. Their roster included artists such as: Eazy-E, N.W.A., Dr. Dre, Above The Law, Kid Frost, Brownside, and Bone Thugs-N-Harmony. The backdrop of this label’s most prolific work was an era of extreme police brutality.

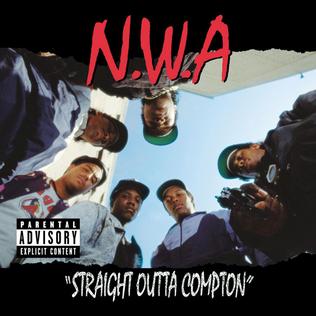

N.W.A.’s breakthrough album was “Straight Outta Compton” which was released in 1988 during a police initiative called “Operation Hammer”. This initiative was led by the C.R.A.S.H. (Community Resistance Against Street Hoodlums) unit of the Los Angeles Police Department and it:

. . . began in 1987 to crack down on gang violence in South Central Los Angeles . . . Operation Hammer heavily employed racial profiling, targeting African American and Hispanic youths that were labelled (sic) as ‘urban terrorists’ and ‘ruthless killers’.

“Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums” Wikipedia

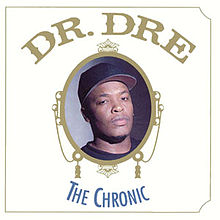

I believe four members of N.W.A. released solo albums right after the 1992 L.A. Riots. This includes Dr. Dre’s iconic album, “The Chronic”. The L.A. Riots were a response to Rodney King’s brutal beating at the hands of the L.A.P.D. which resulted in the officers’ acquittal. These albums were historic social commentary and they have all been removed from the Access Entertainment music catalog.

I grew up in New Mexico as a minority in a single parent home. I lived in poverty and was surrounded by gangs, violence, addiction, and the drug trade as a way of life. When I first heard Hip Hop it was definitely not the cause of any immoral behavior on my part. I finally felt as if someone was speaking for me and I wanted to speak back. The conditions addressed in Hip Hop existed in my life prior to, and contemporaneously with these historic albums.

Police in Los Angeles targeted Black and Brown youth but this wasn’t limited to California. What occurred in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s is probably unknowable because most of these things happened behind closed doors (see “Behind Closed Doors”, W.C. & the M.A.D.D. Circle, Ain’t a Damn Thing Changed, Priority Records, 1991); however, it is safe to say that this violence was reflected in most, if not all of the politically fueled Hip Hop from that place and time. What some people may find surprising is that some of the same officers busting heads in Califas personally spread their gospel to New Mexico agencies as well.

I grew up in Los Lunas bu as a teenager I often stayed in “The Warzone”. This part of town has since been rebranded the “International District” but it’s located in Albuquerque’s Southwest Heights. In the summer of ’95, I knew people from Los Angeles who lived in the Warzone. During this time we were all painfully aware of a white van full of police officers who were known for their gestapo style raids and violence. I didn’t ask questions, I was just informed that was the “Impact Van”.

On one occasion I was handcuffed and choked to unconsciousness by Impact. Another time my head was slammed into the back of a marked car by officers from the Impact Van. That time I suffered a concussion and required stitches on my face. During both incidents all of the money in my pockets was stolen and I was charged with “criminal trespassing” due to the fact that I didn’t live in these locations.

Twenty five years later I have learned the significance of “Impact”. This task force was properly named L.A. IMPACT, which is an acronym for Los Angeles Inter-agency Metropolitan Police Apprehension Crime Task Force.

. . . the brainchild of the Los Angeles County Police Chiefs Association the task force is a compilation of numerous federal, state, and local law enforcement . . .

“LA IMPACT”, State of California Department of Justice

The F.B.I. worked with the Albuquerque Police Department and connected these agencies. I suppose the purpose of that alliance was to train A.P.D. to police like L.A.P.D. I actually gave this task force a dishonorable mention in my own song (see “Varrio”, Ese Spook Loko, 2001). Upon learning of the interagency team-up, I realized that there was a direct, palpable connection to the outcry of N.W.A.’s 1988 album and my own blood on the Albuquerque concrete.

In 1997, Ruthless Records released an album from a group called Brownside. On their album, “Puro Pleito/East Side Drama” they spoke about situations close to my own experience. One song I especially like is called “Life on the Streets” by an artist named Danger. Danger was killed shortly before the album’s release and his song illustrates my point well. Although that artist hailed from another part of the country we shared many commonalities addressed through music. We were hunted by the same task force, and both of our songs are now censored by Google Play. That song about his short, lamentable, but strong life is laced with the cusswords, drug use, and gang affiliation that Google Play hunts for; However, I understood that song as crucial social commentary through art (made possible with help from Eazy-E). That music serves as a testimony to an era but it is now unavailable to the culture who appreciates its significance the most.

My favorite cassette tapes and CDs helped teach me how to process many complex emotions: I learned how to grieve through making music, how to motivate myself through paralyzing depression, and they inspired a healthy aversion to drug addiction. I learned the importance of safe sex practices and was saved from a few bad relationships. That music helped me cope with the racist application of unjust laws and even literally talked me out of committing suicide.

Leave A Comment